King, Martin Luther, Jr. (1929-1968) (1)

As the southern protest movement expanded during the early 1960s, King was often torn between the increasingly militant student activists, such as those who participated in the Freedom Rides and more cautious national civil rights leaders. During 1961 and 1962 his tactical differences with SNCC activists surfaced during a sustained protest movement in Albany, Georgia. King was arrested twice during demonstrations organized by the Albany Movement, but when he left jail and ultimately left Albany without achieving a victory, some movement activists began to question his militancy and his dominant role within the southern protest movement.

As King encountered increasingly fierce white opposition, he continued his movement away from theological abstractions toward more reassuring conceptions, rooted in African-American religious culture, of God as a constant source of support. He later wrote in his book of sermons, Strength to Love (1963), that the travails of movement leadership caused him to abandon the notion of God as “theological and philosophically satisfying” and caused him to view God as “a living reality that has been validated in the experiences of everyday life” (Papers 5:424).

During 1963, however, King reasserted his preeminence within the African-American freedom struggle through his leadership of the Birmingham campaign. Initiated by SCLC and its affiliate, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, the Birmingham demonstrations were the most massive civil rights protest that had yet occurred. With the assistance of Fred Shuttlesworth and other local black leaders and with little competition from SNCC and other civil rights groups, SCLC officials were able to orchestrate the Birmingham protests to achieve maximum national impact. King’s decision to intentionally allow himself to be arrested for leading a demonstration on 12 April prodded the Kennedy administration to intervene in the escalating protests. A widely quoted “Letter from Birmingham Jail” displayed his distinctive ability to influence public opinion by appropriating ideas from the Bible, the Constitution, and other canonical texts. During May, televised pictures of police using dogs and fire hoses against young demonstrators generated a national outcry against white segregationist officials in Birmingham. The brutality of Birmingham officials and the refusal of Alabama governor George C. Wallace to allow the admission of black students at the University of Alabama prompted President Kennedy to introduce major civil rights legislation.

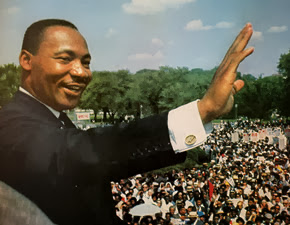

King’s speech at the 28 August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom attended by more than 200,000 people, was the culmination of a wave of civil rights protest activity that extended even to northern cities. In his prepared remarks King announced that African Americans wished to cash the “promissory note” signified in the egalitarian rhetoric of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Closing his address with extemporaneous remarks, he insisted that he had not lost hope: “I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream . . . that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed:‘we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’” He appropriated the familiar words of “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” before concluding, “when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, we are free at last’” (King, Call, 82, 85, 87).

Although there was much elation after the March on Washington, less than a month later, the movement was shocked by another act of senseless violence. On 15 September 1963 a dynamite blast killed four young school girls at Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. King delivered the eulogy for three of the four girls, reflecting, “They say to us that we must be concerned not merely about who murdered them, but about the system, the way of life, and the philosophy which produced the murders” (King, Call, 96).

St. Augustine, Florida became the site of the next major confrontation of the civil rights movement. Beginning in 1963 Robert B. Hayling, of the local NAACP had led sit-ins against segregated businesses. SCLC was called in to help in May 1964, suffering the arrest of King and Abernathy. After a few court victories, SCLC left when a bi-racial committee was formed; however, local residents continued to suffer violence.

King’s ability to focus national attention on orchestrated confrontations with racist authorities, combined with his oration at the 1963 March on Washington, made him the most influential African-American spokesperson of the first half of the 1960s. Named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” at the end of 1963, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1964. The acclaim King received strengthened his stature among civil rights leaders but also prompted Federal Bureau of Investigation director J. Edgar Hoover to step up his effort to damage King’s reputation. Hoover, with the approval of President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, established phone taps and bugs. Hoover and many other observers of the southern struggle saw King as controlling events, but he was actually a moderating force within an increasingly diverse black militancy of the mid-1960s. Although he was not personally involved in Freedom Summer (1964), he was called upon to attempt to persuade the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegates to accept a compromise at the Democratic Party National Convention.

As the African-American struggle expanded from desegregation protests to mass movements seeking economic and political gains in the North as well as the South, King’s active involvement was limited to a few highly publicized civil rights campaigns, such as Birmingham and St. Augustine, which secured popular support for the passage of national civil rights legislation, particularly the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Alabama protests reached a turning point on 7 March when state police attacked a group of demonstrators at the start of a march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery. Carrying out Governor Wallace’s orders, the police used tear gas and clubs to turn back the marchers after they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the outskirts of Selma. Unprepared for the violent confrontation, King alienated some activists when he decided to postpone the continuation of the Selma to Montgomery March until he had received court approval, but the march, which finally secured federal court approval, attracted several thousand civil rights sympathizers, black and white, from all regions of the nation. On 25 March King addressed the arriving marchers from the steps of the capitol in Montgomery. The march and the subsequent killing of a white participant, Viola Liuzzo, as well as the earlier murder of James Reeb dramatized the denial of black voting rights and spurred passage during the following summer of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

After the successful voting rights march in Alabama, King was unable to garner similar support for his effort to confront the problems of northern urban blacks. Early in 1966 he, together with local activist Al Raby, launched a major campaign against poverty and other urban problems and moved his family into an apartment in Chicago’s black ghetto. As King shifted the focus of his activities to the North, however, he discovered that the tactics used in the South were not as effective elsewhere. He encountered formidable opposition from Mayor Richard Daley and was unable to mobilize Chicago’s economically and ideologically diverse black community. King was stoned by angry whites in the Chicago suburb of Cicero when he led a march against racial discrimination in housing. Despite numerous mass protests, the Chicago Campaign resulted in no significant gains and undermined King’s reputation as an effective civil rights leader.

King’s influence was damaged further by the increasingly caustic tone of black militancy of the period after 1965. Black radicals increasingly turned away from the Gandhian precepts of King toward the Black Nationalism of Malcolm X, whose posthumously published autobiography and speeches reached large audiences after his assassination in February 1965. Unable to influence the black insurgencies that occurred in many urban areas, King refused to abandon his firmly rooted beliefs about racial integration and nonviolence. He was nevertheless unpersuaded by black nationalist calls for racial uplift and institutional development in black communities.

In June 1966, James Meredith was shot while attempting a “March against Fear” in Mississippi. King, Floyd McKissick of the Congress of Racial Equality and Stokely Carmichael of SNCC decided to continue his march. During the march, the activists from SNCC decided to test a new slogan that they had been using, Black Power. King objected to the use of the term, but the media took the opportunity to expose the disagreements among protestors and publicized the term.

In his last book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967), King dismissed the claim of Black Power advocates “to be the most revolutionary wing of the social revolution taking place in the United States,” but he acknowledged that they responded to a psychological need among African Americans he had not previously addressed (King, Where Do We Go, 45-46). “Psychological freedom, a firm sense of self-esteem, is the most powerful weapon against the long night of physical slavery,” King wrote. “The Negro will only be free when he reaches down to the inner depths of his own being and signs with the pen and ink of assertive manhood his own emancipation proclamation” (King, Call, 184).

Indeed, even as his popularity declined, King spoke out strongly against American involvement in the Vietnam War, making his position public in an address, “Beyond Vietnam,” on 4 April 1967 at New York’s Riverside Church. King’s involvement in the anti-war movement reduced his ability to influence national racial policies and made him a target of further FBI investigations. Nevertheless, he became ever more insistent that his version of Gandhian nonviolence and social gospel Christianity was the most appropriate response to the problems of black Americans.

In December 1967 King announced the formation of the Poor People’s Campaign, designed to prod the federal government to strengthen its antipoverty efforts. King and other SCLC workers began to recruit poor people and antipoverty activists to come to Washington, D.C., to lobby on behalf of improved antipoverty programs. This effort was in its early stages when King became involved in the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike in Tennessee. On 28 March 1968, as King led thousands of sanitation workers and sympathizers on a march through downtown Memphis, black youngsters began throwing rocks and looting stores. This outbreak of violence led to extensive press criticisms of King’s entire antipoverty strategy. King returned to Memphis for the last time in early April. Addressing an audience at Bishop Charles J. Mason Temple on 3 April, King affirmed his optimism despite the “difficult days” that lay ahead. “But it really doesn’t matter with me now,” he declared, “because I’ve been to the mountaintop [and] I’ve seen the Promised Land.” He continued, “I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.” (King, Call, 222-223). The following evening the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. took place as he stood on a balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. A white segregationist, James Earl Ray, was later convicted of the crime. The Poor People’s Campaign continued for a few months after his death under the direction of Ralph Abernathy, the new SCLC president, but it did not achieve its objectives.

Until his death King remained steadfast in his commitment to the radical transformation of American society through nonviolent activism. In his posthumously published essay, “A Testament of Hope” (1969), he urged African Americans to refrain from violence but also warned, “White America must recognize that justice for black people cannot be achieved without radical changes in the structure of our society.” The “black revolution” was more than a civil rights movement, he insisted. “It is forcing America to face all its interrelated flaws-racism, poverty, militarism and materialism” (King, “Testament,” 194).

After her husband’s death, Coretta Scott King established the Atlanta-based Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change (also known as the King Center) to promote Gandhian-Kingian concepts of nonviolent struggle. She also led the successful effort to honor her husband with a federally mandated King national holiday, which was first celebrated in 1986.

Hope you you enjoyed reading my post & found it

useful

You may be also interested in

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment